by Leila Taleb

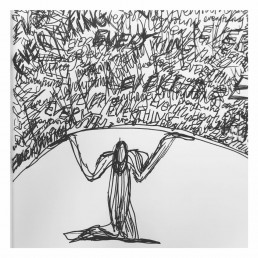

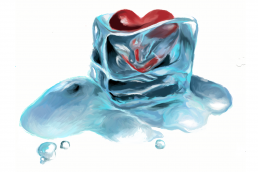

Image credit: Annie Rew Shaw

A Google search for ‘mental health at the bar’ or ‘mental health for bar students’ usually gives you the websites of barristers chambers advertising their best advocates in mental health law. There is little to be found on the mental health of those driving the profession; or students aspiring to be part of it.

With Bar Professional Training Courses (BPTC) courses now issuing health warning disclosures to prospective students upon applying to go to bar school, the bar is perceived as a profession whereby you enter at your own risk. This is evidenced by the immense amount of blogs and websites that warn you to only aspire to the bar if you think stress can be your best friend.

Before I even applied, I had several doubts about whether I was enough for the bar, particularly when going into a profession that is perceived to be comprised of a socially conservative pool with a sea of the same faces from the same places. Yet, it is only when the bar reflects the true diversity of our population that our justice system will be more trusted and transparent.

We may look (and at times feel) like black-caped superheroes of justice, but we are not; we are human. Being a barrister or bar student involves a substantial amount of independent work, which can often be isolating, with only the likes of Instagram to keep you company. So the question remains – who do we turn to for help when we are struggling?

You would think one another. Well, think again.

Even if people take the courage to write about such issues, you get procrastinating trolls claiming how people with any sort of mental health issue will never be suitable for the bar and that revealing such emotions is self-inflated and obnoxious. God forbid a woman who is self-assured enough to talk on behalf of others about taboo topics (that amongst many men remains untouched).

Research shows that women are more likely to suffer from mental health problems than men, caused by many factors including domestic violence, income inequality and carrying the assumptive burden of family care commitments whilst trying to maintain one’s own progression on the career ladder (I know, anyone would think men are also parents). However, we do know that men are less likely to report or express that they are suffering due to the socialisation of what it means to be a ‘man’ or a ‘woman’. Suicide rates are also higher for men due to the lack of opportunity for them to express themselves and be vulnerable.

Feminism and gender equality benefits men and women in breaking down such harmful barriers to expressing oneself individually, yet men are lacking in the fight for such equality. We may be on the way to raising more empowered girls and women but we must not neglect to also empower boys and men so that they are also not confined to their pre-destined roles of being the ‘breadwinner’ or the macho male.

Women and girls are often encouraged to become doctors or a professional football player and to not let stereotypes hold them back, yet men are never encouraged to take up ballet or have more caring responsibilities. That is because ‘feminine’ is analogous to being of lower status.

Men can’t show emotion but can be angry, which is reflected in men’s tendency to take out their problems through external mechanisms like drugs and alcohol. Yet, women are taught to be emotional but not show anger, which is why they often take stress out on themselves. Our drive to have a more equitable society is part of the drive to have discussions on stress-management and mental health.

Mental health is not just a social stigma but, on one’s journey to the bar, it is viewed as a badge of weakness that nobody wants to associate with. Yet everyone has mental health problems, just on different spectrums with different life-events triggering symptoms more so and at different times to others. So whether you like it or not, we all carry the badge.

Too much oxymoronic pride is taken in being a busy bee and not getting the recommended hours of sleep a night. All of us gossip about the ridiculous amount of work on the course but we deal with it by trying to laugh it off, silently crying in class or just before bed with our only consolation being the copious amounts of wine served at the late night legal events, momentarily taking away the shroud of worry away.

No time to exercise, cook and days starting and finishing with your books at the side of your bed. Re-reading the sentence ten times before you can take what you read in due to exhaustion or anxiety at the thought of running out of time. You are forced to hibernate from any other sort of responsibilities and extra-curricular work you may have; yet feeling anxious about how you are letting others down.

This is not to mention those that have to work to support themselves through the BPTC, who often tell me they get a few hours sleep on a night. Unlike other postgraduate courses, you don’t get a Student Finance loan from the government to cover the £15,000 cost of a 9-month course despite the course being recognised as a postgraduate one. So, in order to accommodate students who depend on that loan to pay for the course alone, universities are offering a BPTC combined with a LLM to qualify for Student Finance, which ultimately means more hours on top of an already overwhelming course for those with less time and money.

This mental stress takes its toll on physicality, with students having to get glasses, developing anxiety, taking antidepressants, stress-related acne problems, and feeling physically fatigued. You wonder how your body manages to ache when you haven’t lifted any weights for six months or done any form of hard exercise at 20-something years old. Since then, I have realised that exercise isn’t about the booty; it’s about the brain.

For students who have not yet attained pupillage (traineeship to qualify as a barrister), the thought of opening up that they feel overwhelmed by the amount of work on the bar course is preposterous.

Admitting that you can’t cope at such a preliminary stage to teachers who are barristers themselves, who are married to barristers and whose closest friends are barristers, seems like an irrational idea if you want to get a job in a climate where competition is ‘dog eat dog’.

If we don’t learn to open channels to talk about the mental health of students, alongside breaking down constrained gender barriers and instilling stress-management techniques from a young age, then this problem will continue.

Stress is a killer. Your body and mind are attuned to act as one and if you don’t look after both, your body will cease to function and you will no longer be around to do the very job that you are living for. Any career is a career; it shouldn’t take your life.

One’s suffering is not in vain and nobody should ever feel shameful for it, because overcoming it is often part of who we are or who we are yet to become.

Leila Taleb

Leila is currently working towards pursuing a career as a barrister. In the meantime, she wears many hats in the local community and is particularly passionate about women’s rights. She is Chair of JUST Yorkshire: a civil liberties organisation that campaigns on issues pertaining to racial justice. She is also co-founder of Same Skies Collective: a group that mobilises members of the public and civil sector representatives on devolving power to the North. She is a member and one of the original founders of Speaker’s Corner, which is a creative social space in Bradford led by women and girls that campaigns on social justice and women and girl’s issues; and is also Chair of the Anah Project, a domestic violence refuge for Black and South Asian women. She loves to throw mad shapes on the dancefloor in her spare time.

Annie Rew Shaw

Annie is a musician, artist and writer from Devon, now based in North London. She performs and releases music under the moniker Austel.

Her poetry, illustrations and music serve as a cathartic outlet; depicting the vivid physical and verbal imagery that we can use to articulate mental health and human emotion.