by Emma Berry

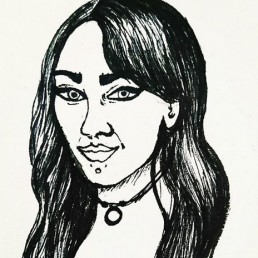

Image credit: Anna Coughlan

I recently finished my master’s thesis on why accommodating the needs of trauma sufferers in universities is an issue of justice and equality. If I wasn’t already convinced that this was an important topic, the response to my proposal was enough to assure me.

When I started filling out the ethical considerations form, I was told that an ethics form wasn’t relevant to my topic because it was on theoretical politics. This failure to recognise the effects of trauma on everyday life, or to consider that such research may be psychologically upsetting, is indicative of the lack of awareness within education of how study material can have a profound influence on the lives of students.

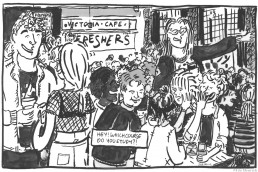

Up to 50 percent of university students have experienced trauma,1 and members of oppressed groups are disproportionately affected, due to factors such as the prevalence of violence against women, racially motivated attacks and hate crimes.2 So actually there was a good chance that I would be affected by what I was writing about, as a female student and a member of more than one oppressed group.

Trauma theorist Bonnie Burstow states that trauma is ‘inherently political’.3 Trauma is pervasive in the lives of women; even if women haven’t personally experienced gendered trauma they will most likely know someone who has, meaning we experience what Maria Root terms ‘insidious trauma’.4 This refers to the process of being socialised to live in fear of violence, which subtly influences our responses to situations: for example, feeling fear in response to being hit-on, rather than taking it as a compliment as some argue we should. In this way, women who have never experienced trauma are influenced by its pervasive presence.

It therefore seems all the more unjust that the needs of traumatised individuals are not taken seriously. Triggering is a spontaneous reaction characterised by a range of uncontrollable physical or emotional responses that affects those who have experienced trauma.5 Trigger warnings, intended to prepare trauma sufferers for triggering material, are now treated as something of a joke in online circles. Requests for their use by students have been widely rejected, notably by the American Association of University Professors, which treats triggering as ‘discomfort’.6

This is hard to accept as a woman or as a member of any oppressed group. We are beaten, raped, abused, threatened on a daily basis, told not to walk home alone because we will be attacked; we are underestimated, underpaid, underemployed, objectified and patronised. On top of this we are then told to ‘toughen up’ and laughed at when we request measures to help us deal with the oppressive hand that society has dealt us.

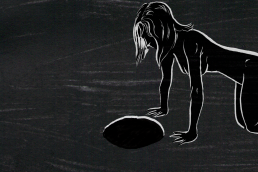

Trauma sufferers are tough. I don’t mean this in an encouraging, motivational way; trauma nurtures resilience. When one experiences a traumatic event, the brain adapts to its environment to prepare for survival in the future.7 When this happens in childhood, the developing brain changes so that this fear response becomes a trait; trauma sufferers are built to survive.

When you think about who you are, a fundamental part of that identity is likely to be grounded in your family, socialisation and memories. But what if those associations are tied up in traumatic events? It isn’t just a case of getting over it because, to some extent, we are shaped by our trauma. That is not to say that trauma cannot be overcome but that it will remain a key part of who we are, for better or for worse.

Much of being a member of an oppressed group is a lived experience; not one which can be summarised as a short narrative. It is so subtle and socialised, that a great deal of the time, members of oppressed groups do not consciously acknowledge feelings of fear or discomfort, for example when being objectified or cat-called, because it is a constant state of being. Trauma is similar, not only in the sense that trauma sufferers are more likely to be members of oppressed groups but because responses to trauma are developed for self-preservation.

We often fail to recognise the importance of trauma as an issue both because its nature is rooted in denial, but also, and more importantly, because those who are not members of such oppressed groups cannot fully understand the trauma of socialisation. These factors result in a lack of understanding which accounts for the negative response with which trauma is often met.

As with so many issues of social justice, it seems that the solution is increasing awareness; awareness of what trauma is and involves, what triggering is, and why trauma is so pervasive. More than anything, this awareness needs to include the recognition that the requests of trauma sufferers may not always make sense to others. This is not to say that we must accept all requests for accommodations; there are important considerations such as freedom of speech and legal and moral implications. However, the outright refusal to look for areas of compatibility between the needs of trauma sufferers and the implications of this refusal demonstrate a failure to even attempt to understand the life experiences of trauma sufferers and, by extension, oppressed groups.

1 http://www.apa.org/monitor/2014/07-08/course-distress.aspx

2 Brown, L. (1995) ‘Not Outside the Range: One Feminist Perspective on Psychic Trauma’, in C. Caruth (ed) Trauma: Explorations in Memory, Baltimore and London: The John Hopkins University Press, pp100-112, at p106.

3 Burstow, B. (2003) ‘Toward a Radical Understanding of Trauma and Trauma Work’, Violence Against Women 9 (11) pp.1293-1317, at p1306.

4 Root cited in Brown (op cit) p.107.

5 Carter (2015) http://dsq-sds.org/article/view/4652/3935#endnoteref22

6 AAUP (2014) https://www.aaup.org/report/trigger-warnings

7 Perry, B.D., R.A. Pollard Toi, L. Blaicley. W.L. Baker and D. Vigilante (1995) ‘Childhood Trauma, the Neurobiology of Adaptation, and “Use-dependent” Development of the Brain: How “States” Become “Traits”’, Infant Mental Health Journal, 16(4), Winter.

Emma Berry

Emma has been writing articles since she was 16 for a number of platforms. She completed a Master’s degree in Legal and Political Theory at University College London in 2017, for which her thesis title was: ‘Why should the university give trigger warnings? Balancing justice and equality with non-repression and free speech’. Emma continues to write about and research the political significance of trauma in her own time, as well as working for a child advocacy company.

Anna Coughlan

Anna is an aspiring comic artist who studied Fine Art at Crawford Art College in Cork, Ireland. She then pursued her passion for comics and graduated from the Comics Studies MLitt course at Dundee University. Shortly after she graduated from her masters, she decided to stay in Dundee to utilise the facilities of the Dundee Comics Creative Space and Ink Pot Studies comic community. She is now living in Edinburgh teaching art to elderly people who suffer from dementia.

Her work is predominantly traditional and most of her work is black and white. She dabbles and hopes to progress into a more digital art style. She loves all things that are gothic, and especially likes working under the themes of horror and science fiction.