Ellen Desmond

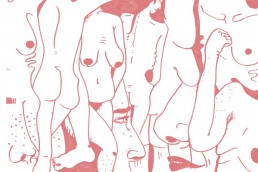

Illustration by Ida Henrich

Content Warning: brief mentions of sexual assault

A while back, I watched a Ted Talk called The Virginity Fraud by Nina Dølvik Brochmann and Ellen Støkken Dahl — authors of the book The Wonder Down Under — and realised I should be concerned about virginity, but not in the way you might expect.

Getting right to it, I’ve now decided I don’t really believe in virginity at all. I’ve come to think virginity’s a very damaging social construct causing many people to suffer, and one which erases queer experiences while also placing pressure on asexuals to conform or feel excluded. In sum, I no longer feel there’s a basis for believing virginity is measurable and, more importantly, I don’t see why even the most progressive among us are so quick to want to measure it; after all, the matter boils down to policing female sexuality and commodifying women and who needs those delights as part of their value system?

It’s been interesting to pause and evaluate what virginity means, exactly. Can only women be virgins? Can a person only lose their virginity through penetrative, heteronormative intercourse?

It’s been interesting to pause and evaluate what virginity means, exactly. Can only women be virgins? Can a person only lose their virginity through penetrative, heteronormative intercourse? What if it’s orgasm-inducing queer sex that doesn’t involve a penis (or that only involves penises…)? Sex arguably varies as much from partner to partner as it does from gender to gender, so, sexually active queer people can hardly be considered virginal. And what about if a person doesn’t consent, and it’s a case of sexual assault? Who has the right to take away a label another person’s not offering?

The issues and standards surrounding virginity are emotionally heavy for most people, to varying degrees. In some instances, it’s the social and peer pressure to have sex before you’re ready; in others it’s feeling judged if you’ve not had sex yet when you do want to. There are also cases where people feel forced to deprive themselves of healthy sexual experience, or are judged harshly for having “too much” sex. Both virgin shaming and slut shaming are common forms of bullying and retaining a patriarchal status quo, but in reality there’s no living up to the “correct” sex-life standard. Unfortunately, women particularly are too often chastised every which way is their own unique reality.

Messages around virginity can also be hugely problematic due to their focus on hymen loss, virginal bleeding and pain and, at the other end of the scale, there’s little positive information in sex-ed and general discourse about achieving orgasm. I always thought the first time was definitely going to hurt me — as a woman — but be a great experience for any potential male partner. While first-time sex may hurt (and the reasons for that vary from nerves through lack of lubrication to having no idea what you’re doing) it doesn’t have to hurt.

Much of what we’re traditionally told about virginity tends to begin and end with hymen matters and the folklore playground tales around this are, in my experience, generally alarming for women, at best. What I didn’t know till I left education is this: the hymen’s a rim of tissue deep in the vagina, and is generally very misunderstood anatomically — mostly because of the social constructs surrounding women’s virginity. We tend to think of the hymen as something that rips or gets lost the first time a woman has intercourse — resulting in a “loss of virginity” — but that’s not always the case. The hymen tends to take different shapes in different people, and is rarely the “seal to break” (though it can be, and this condition is called an imperforate hymen). It’s often a half moon shape, or an elasticated hoop with an inner space, and can even be present in the form of parallel lobes. Every hymen is different, and as a result, not all will bleed or tear upon first intercourse — many are strong enough to withstand bleeding, others stretch to accommodate penetration. Many more still may be previously altered by tampon use, masturbation, or strenuous exercise.

This is a colossal problem because, as well as anatomy myths not being addressed in 2018, in many places across the world these same myths mean women are subjected to virginity tests, placing them in serious danger and often resulting in honour killings if bleeding doesn’t happen on a wedding night. “The anatomical truth [about hymens] has been known in medical communities for over 100 years”, according to Brochmann and Dahl — so why do centuries of different cultures disregard the facts and place women in danger? It’s yet another element of patriarchy, one directly linked to the availability of tightening creams and “fake your virginity now!” vaginal blood tablets. It’s shocking that people are forced to go to such extremes and further harrowing that others are profiting from that danger. Then, in parallel, there’s the heartbreaking consideration that these products are also secretly saving women’s lives.

Our sex lives (or lack thereof) affect our wellbeing in a multitude of ways. Sexual expression and sexual self-image are vital to the relationships we have both with ourselves and others.

So why is all this relevant to a feminist discussion on mental health? Our sex lives (or lack thereof) affect our wellbeing in a multitude of ways. Sexual expression and sexual self-image are vital to the relationships we have both with ourselves and others. We know that increasingly, many people find it difficult to have sex because of mental health challenges, and many LGBTQ+ people have their experiences hurtfully shunned as lesser by mainstream understanding of virginity too — enforcing heteronormativity as the only valid sexual activity can lead to feelings of extreme degradation.

It’s revealing to stop thinking about sex through the default lens of something most commonly centering male pleasure, and how that same view often disregards, belittles and shames trans, non-binary and women-loving-women experiences.

The links between purity and virginity become extremely unfair and unfounded when we consider cases of rape and childhood sex abuse too, events that can have a huge effect on a person’s mental health, especially when it comes to developing Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and anxieties.

There’s no time when we should judge someone for losing their virginity if they choose to, but we definitely can’t judge someone when it wasn’t their choice to begin with. All things considered, isn’t the term arbitrary now anyway?

There’s no time when we should judge someone for losing their virginity if they choose to, but we definitely can’t judge someone when it wasn’t their choice to begin with. All things considered, isn’t the term arbitrary now anyway?

The social and peer pressures surrounding the virginity construct can cause stress, bullying, relationship difficulties, prejudices, male entitlement to female bodies, erasure of queer people and distorted levels of self-worth. Beginning a sex life is a milestone and we should go ahead and treat it as such if we wish, but this one is out of control — which other rites of passage do we evaluate, punish or judge to such an extent? We need to drop the assumption that virginity equates to some sort of superior purity, and stop patronising those with less sexual experience too.

I’m a fan of Lauren’s Forster’s attitude: “You lose your keys, not your virginity”. I think we should all refuse to see virginity as a vital qualitative measure, or reflection of someone’s worth — sexual or otherwise. Anxieties about sex are already very real. It’s time to stop making things worse by perpetuating myths.

Ellen Desmond

Ellen Desmond grew up in Ireland, where she worked at editorial and project management level on various magazines and publications aimed at students. She was awarded the title of Ireland’s Best Student Editor in 2016, just before she moved to Edinburgh to complete an MSc in Publishing. While writing her dissertation, she co-edited and published a popular anthology about bisexuality. She is a passionate intersectional feminist, and an advocate of mental health reform and LGBTQ+ rights.

As Deputy Editor at Fearless Femme, Ellen is responsible for co-ordinating, creating and editing great content, and conducting research on the mental health of young people to support our social mission of breaking down mental health stigma.

In her spare time, Ellen loves reading and trying to prove that she’s read more than you. She also loves activism, art, going to music gigs and, more occasionally, skydiving. She hates oranges and spiders. You can contact her at ellen@fearlessly.co.uk.

Ida Henrich

Ida Henrich is a German Cartoonist, Illustrator and Designer based in Scotland. She has worked with award winning publishers, online coaches and magazines. Ida is a graduate of Communication Design at the Glasgow School of Art where she specialised in Illustration. In her own work she explores themes such sex-education, growing up, and women’s experiences. Her comics and illustrations are written for both men and women and aims to start an open dialogue between partners, friends, parents, and children about their one’s own experiences. She believes that Art is a powerful way to make ideas and feelings tangible.

As Art Editor, Ida is responsible for all things visual at Fearless Femme including the correspondence with our visual artists, the design and realisation of the online magazine and the illustration of our amazing cover girls. She will also be creating artwork for some of our articles, poems and stories.

Ida loves her coffee in the morning, that feeling after finishing an illustration and going for a run in the (Scottish) sun; and pilates on the rainy days. Ida enjoys SciFi books and autobiographies, and autobiographical comics. She is always delighted to meet new people on trains but is also smitten being home alone colouring in an illustration that she has made way to intricate while listening to Woman’s Hour. You can contact her at ida@fearlessly.co.uk.