By Dr Eve Hepburn

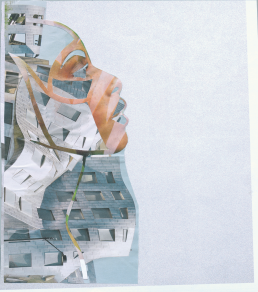

Art by Sharon Walters

As global politics seems increasingly driven by populism and self-interest, and we’re all fatigued by the constant state of uncertainty and disbelief as to how we got here, our need for a leader we can believe in has never been stronger. A leader who understands the benefits of uniting people rather than dividing them. A leader who wants to create communities of empowered individuals rather than protecting the interests of the few. A leader who is a feminist, a peace-maker, a bridge-builder, a community-builder.

Step up, Michelle Obama.

Lawyer, civil servant, non-profit activist, university administrator, mother, wife, daughter and of course, the first African-American First Lady of the United States of America.

Although her reign of the White House, with husband 44th President Barack Obama from 2009-2017, seems to have happened years ago in a distant galaxy (given the current misogynist and backward-looking leadership of the USA), Michelle is not far from our minds. That’s partly because she’s been back on the world stage marketing her first autobiography, Becoming, which gives insights into how the White House used to run that made my heart contract. But it’s also because Michelle has become a symbol of a different type of world, far removed from the white, privileged, patriarchal model we are currently lumped with.

Unlike the vast majority of those who went before (and after) her, First Lady Michelle was not born with a silver spoon in her mouth. She grew up in urban Chicago as the daughter of working-class parents, and through her ambition and determination to use her state-funded secondary education to her advantage, went on to attend Princeton and Harvard before embarking on a career in corporate law and later, public service. From her autobiography, you get the feeling that Michelle was never one to take no for an answer; “I was the kind of kid who liked concrete answers to my questions, who liked to reason things out to some logical if exhausting end. I was lawyerly and also veered toward dictatorial, as my [older] brother, who often got ordered out of our shared play area, would attest.”

But Michelle’s iron will was bent towards helping others rather than individual self-interest. Her career choices reflected the passions closest to her heart: helping disadvantaged kids get equal rights to education, helping girls and young women get a head start in the world, helping families get healthier through their food choices. But the thing that makes her legacy stand out has been her unfaltering belief in the value of community.

Before she became First Lady, Michelle sought out roles that would allow her to not only give back to the communities that nurtured her growing up, but to encourage everyone to see the value in helping others less fortunate than themselves. She became the Executive Director of the Chicago chapter of Public Allies, a non-profit that encourages young people to work on social issues in community organisations and government agencies. She then became an associate dean for community and external affairs at the University of Chicago, which became committed “at long last to do a better job of integrating with the city … through the creation of a community service program to connect students to volunteer opportunities in the neighbourhood… The chance to try to lower those walls… was one I found inspiring.”

When Michelle Obama became First Lady, her efforts to build communities and encourage people to take up the mantle of public service only increased. She set up programmes like Let’s Move, which brought together community leaders, educators, medical professionals, parents and others in a nationwide effort to address the challenge of childhood obesity; Reach Higher, which sought to encourage all young people to complete their education beyond high school; and Let Girls Learn, a US government initiative to help girls around the world go to school and stay in school. Even the school she chose for her children to attend in Washington, D.C. was selected because its philosophy was “all about community, built around the idea that no one individual should be prized over another.”

Why was community so important to her?

A speech to the Corporation for National and Community Service in 2009 gives us some insight. Michelle said that “there is nothing more fulfilling [than community service]. It’s an opportunity to put your faith into action in a way that regular jobs don’t allow. For many Americans it may seem impossible to squeeze even more time out of the day and do more. But I still strongly encourage people to think about volunteering.” But she also acknowledged the limits of volunteering, especially for those without the financial means to do so. “When I was coming up, volunteering and doing an internship seemed to be a luxury that working-class kids couldn’t afford,” she said. “It is so important that young people, regardless of their race or their age or their financial ability… have a chance to serve.”

By advocating the value of community service – of being and giving to something larger than yourself – Michelle Obama was perhaps unknowingly endorsing one of the most important means by which positive psychologists believe we can safeguard our emotional wellbeing: through community belonging and community service. Mental health experts have long been arguing that when people feel part of a community, and when they donate their time and energy to a greater social cause, they feel better. This is because community belonging reduces our sense of isolation and loneliness, while volunteering for a worthwhile cause gives us a sense of purpose that we’re often unable to find in our daily jobs.

In other words, if we’re able to switch our focus from our self, to the bigger community of which we are actively members, this can make us feel more connected and valued.

This is an important proposition. We know from research that loneliness and isolation amongst young adults is rising steeply in the UK. With advances in technology, our connections with other people have changed – so we’re more likely to text or Whatsapp someone than meet them face-to-face for a cuppa. Our isolation in turn makes us feel like failures – as if we’re not doing what society expects us to do. And this isn’t helped by social media and the ‘faking’ of public happiness on Instagram and Facebook. So what can we do?

If we listen to Michelle Obama, then we have to reinforce the community structures that embed our sense of emotional belonging and self-worth, which seem to have eroded over the last few decades. We need to make it easy for young people to connect with each other and to create the everyday social relations that allow people to meet in an organic way. We need to foster community relations between people of different generations, so we can experience life-learning, sharing and different perspectives. We need to invest in our community groups, our local organisations, our social spaces. We need to make it possible for people to volunteer for worthy causes alongside (or as part of) their day jobs. And we need people to recognise that we are ultimately social animals – we cannot exist in isolation.

Michelle Obama has perhaps inadvertently put her finger on one of the most troubling and growing epidemics in the developed world: the decline of community. The economic system we’ve adopted, which espouses individualism, self-interest and the accumulation of individual wealth, is making us lonely, isolated and mentally unwell. What we need to do – for our own wellbeing and for everyone around us – is to realise something the philosopher Leonard Peikoff once said:“the individual has reality only as part of the group, and value only insofar as he serves it”. Only through working together, as part of a community, can we make the social change needed so that everyone feels they belong. Michelle has taken us a long way to achieving these goals; now it’s up to all of us to carry on the mantle.

Dr Eve Hepburn

Eve Hepburn is a native Edinburger who has held research and teaching positions at several universities. She loves chilling out with her family; trail running through the Cairngorms; reading and walking her dog.

Sharon Walters

Sharon is a Black British artist of Caribbean heritage. She has a degree in Social Sciences from the University of West London, a degree in Fine Art from Central St Martins University of the Arts and a Postgraduate teaching certificate in post-16 citizenship education from the Institute of Education. Sharon’s studies have informed her art practice in particular her interest in race, identity and gender politics.