by Charley Hines

Image credit: Ashling Larkin

My earliest memory is of my dad lifting me up to peek over the edge of my sister’s cot in the hospital. Among the sterile, white walls and the scratchy pale green blankets she was a warm, glowing little creature that I loved on sight, and didn’t know why.

I didn’t struggle to be a big sister. I wasn’t jealous. I am told “you just loved her, you just loved her.” I remember that, in the absence of very many other discernible memories from my early childhood. This overwhelming sense of something larger than I could comprehend, a settling on my shoulders – it felt a little like wearing a fancy new backpack for the first time.

We take on a responsibility, we eldest-ones, that both is – and is not – ours to bear. We should know better — but maybe we don’t, because we are just children too.

We are not their parents, but they look up to us as all-knowing, wise, and knowledgeable in a way that is never quite as true as either of us want it to be. I was a very late bloomer to dating and sexual exploration, and when it became apparent that my sister had experience of things I didn’t, I was appalled with myself. I felt I’d let her down.

When things get tough in a family, particularly when a younger sibling is suffering, being comfortable in one’s position as the Eldest can get extremely tricky. There is nothing more skin-crawlingly frustrating than watching someone younger than you go through something that you just don’t yet have the life experience to fully understand, let alone help to fix. I was consumed with the need to show her how life was done.

My sister and I were — are — chalk and cheese. We don’t even look alike. She gets angry, I get sad. She could nap for England, I struggle to sleep at night for fear of missing out. She’s a social butterfly, I would rather spend a cosy night in alone. We have three things in common: The love of our parents, our love of Harry Potter memes, and our combined determination that we must never, ever wind up with the fractured relationship that my Mum’s two brothers share. With this fragile surface connection, we could go our separate ways amicably — at first. It would break our hearts before too long.

Our habitual squabbles and petty arguments came to an abrupt end when I took the plunge and worked abroad for an extended period of time — we both experienced the sobering and gutting heartache of what it is like to be without someone who has been around for as long as you can remember.

Our fights nowadays are blue-moon rare, but they shake the roots of our family home, and our words brand themselves into our hearts. Our childhood pact to never end up like my Uncles – bitter, resentful and isolated — keeps us together in a way that is both immortal and claustrophobic in it’s importance.

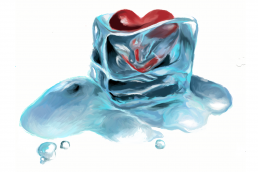

To end a relationship with a lover is to break through a wall that keeps you from growing. To end a friendship is to gracefully turn the page of life, to let go of what was, be it a favourite chapter or one you are glad is over. To break bonds with a sibling is to stand at the top of a skyscraper, and drop a priceless vase from the edge. There is no end of people who see the drop and have their opinions on how it happened. A hundred different theories, no-one is quite sure how it came to this. But what is certain is that when the vase finally hits to floor, the flying shards are a danger to anyone who happens to be nearby — cousins, aunts, uncles, yourself — and anyone lucky enough to not actually be pierced by a shard becomes a little more wary, a little more cautious.

What is it to be Sibling? Now that I have unlaced the corset of “shoulds” that society gave me and let my whole self breathe, my masculine and feminine and the bit in between. Sometimes sister, quietly brother, always flesh and blood, always sibling.

We have gained more common ground as we have grown — mental health problems have hung heavy over both of our adolescent years. I love her more than I have ever loved anyone, even — and perhaps especially — when I have disliked her so intensely that if this were a romantic relationship, I would have broken it off.

There is more of this story, many years of it, still to come. Now that we have realised how much it would hurt to truly be without each other, we are quietly more forgiving, more caring, more sensitive to the other’s needs. We would go to the greatest of lengths for this person with whom we would barely give a second glance if we weren’t related.

It is bizarre, it is frightening, it is the truest sense of home we will ever know. Things get fraught, and confusing, and frustrating sometimes, but all we have to do, to move on, is think of our Uncles and chant our mantra:

Let’s not be like them, let’s not be like them, let’s not be like them.

Charley Hines

Charley is an actor and broadcaster living in London. They have recovered from severe depression and anxiety, and they are working to improve the mental health conversation within the performing arts business. When Charley isn’t treading the boards, they can be found ukulele-playing, clarinet-tooting, book-reading, puppet-wrangling and city-walking.

Ashling Larkin

Ashling is a Scotland-based comic artist, illustrator & animator. She graduated in 2016 from DJCAD with a 2:1 Bdes(Hons) in animation and has since been doing freelance work at the Dundee Comics Creative Space at Inkpot studio while also working on her current ongoing project, a fantasy-adventure webcomic called “The Enchanted Book”.