by Kiran Sidhu

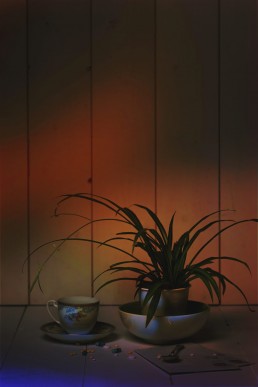

Image credit: ‘Illusions of everything being just fine’, by Kathryn Polley

It’s been three years since I lost my sixty-two-year-old mother to cancer, and at times I still feel the intense pain of grief. It occasionally hits me like a truck and leaves me longing for her. A friend thinks I should consider taking the anti-depressants I had taken in the first few months of grief, but I don’t agree with him. I feel they paper over what are probably the most raw and authentic feelings I have ever felt. I don’t enjoy the sporadic and visceral pain that comes with grief, but I don’t want to numb the pain; it has its place.

Sometimes feelings of sadness and grief can overwhelm us until they are no help to anyone, and in those instances, perhaps it’s right that we numb the pain that has become too destructive for us to occupy. But I believe at times it’s only right and natural that we allow ourselves to feel pain; to deny it is to deny the natural reaction to deep loss and hinder the development of our very beings.

Grief needs to be honoured before it can be transitioned into something new. I now function just as I did before my mother died, I have come to the point where I mostly control my emotional anguish. The background music of my life has changed and I accept that it is now something that is part of me – sometimes it’s just a murmur and at other times it speaks in tongues; all consuming and mercurial. I feel I have accepted this more readily than those around me.

Feelings such as sadness and sorrow are ushered along in our lives; ‘it doesn’t do well to dwell.’ Such feelings are greeted with bland expressions such as, ‘life must go on.’ We have no time to wait in the interim room of sadness – we are not allowed to sit in its stillness and feel its cold hand upon our shoulder. But feelings of sadness and sorrow are just as valid as feelings of happiness, excitement and contentment; they too have their rightful place. However, instead of giving ourselves permission to feel difficult emotions, we divorce ourselves from them; we try and distract ourselves from their presence by eating the family-size slab of chocolate or looking at our phones.

It sounds obvious, ‘we must take the rough with the smooth,’ – but it’s not what we do. We fail to examine our most difficult feelings: to do so would be to stare into the abyss. C.S Lewis’s revered account of his grief in ‘A Grief Observed,’ shows how Lewis befriends his grief and marvels at it as if it’s a new part of his external body. Like a Rubik’s cube, he takes his time to examine the multifaceted emotion of his grief. And yet he’s only doing something with his sadness that we all eschew: he sits with it.

It is generally accepted that there are some things in life that can make you, yet the opposite saying, ‘somethings in life can break you’, sounds defeatist. But some things do break you and strip you down to your very core. Why do we find it so hard to admit that some things are so damaging, that the embers from the fire of their experience can singe the remaining years of our lives? Some things do break you and force you into an existential crisis, and maybe sometimes you do come out stronger, but sometimes the experience just crushes the person you once were. And that’s OK; some experiences, in their greatness, can only ever leave you broken. But this isn’t always necessarily detrimental.

I may live in the shadow of my mother’s early death, but I feel I have acquired an acute awareness of life. I have never felt things, both sad and happy, so profoundly and my heart has never been more open. I’m sure I never noticed the chill in the air with autumn’s approach as much as I do now.

Since her death, I have been heavily involved with Macmillan Cancer Support – appearing in their posters and radio adverts. I have never written with so much honesty; I have openly bled onto my keyboard. I never hit the proverbial bottle or felt the need to numb my pain in that way. I have only dared myself to feel. Everyone has their own story, the story that made the front page of their life, the day everything changed; when the musical notes of their life were rearranged. The day their life was divided into a ‘before’ and ‘after’. I have learnt that it’s important to sit and allow myself to feel my loss, no matter how long it takes. Some things take a lifetime, and that’s OK. I have discovered: in stillness lies the truth.

There’s no shame in allowing our hearts to break, to break in great visions of natural beauty, in song lyrics, while we read epic books, over sunrises and sunsets, and when we have lost people we have loved. It’s at these moments, when we allow ourselves to be shipwrecked, that we come alive. Hearts, after all, are meant to feel. And in the great words of the Wizard from The Wizard of Oz: “Hearts will never be practical until they are made unbreakable”. Vulnerability and authenticity does not make us weak, we do not have to stare helplessly into the abyss. We can swim in it, and take long and elegant breaststrokes in its ebb and flow. The abyss belongs to us.

The philosopher, Arthur Schopenhauer, believed life is full of suffering: “possession takes away the charm.” Seldom do we bask in the sunshine of happiness long before we seek it elsewhere – in our next holiday or our next paycheque. Happiness is so often fleeting. We never really question happiness like we question our pain; we never corner it and ask it, ‘why me?’. Perhaps it’s because we think it rightfully belongs to us and it should be our reigning emotion.

But we’re not simple creatures. We’re a melting pot of an eclectic mess of emotion, with each emotion fighting for a place in our lives. Happiness is elusive and flutters like a butterfly, while sadness sits on us like a sumo wrestler. Its presence disturbs and offends us so much that we’ll do anything to silence it: the extra glass of Pinot Noir, cake, Prozac. If happiness is fleeting, and we have a habit of numbing our pain, in the end, we never allow ourselves to really feel anything at all. We’re human pinball machines, catapulted into the next distraction. And we may as well be a nation that has just overdosed on Prozac. We must embrace all of our emotional spectrum. To neglect it is to have a life that’s been half-lived, or at least half-felt.

In Japan, they have an art of repairing broken pottery, it’s called Kintsugi. They repair the broken ceramic with a special lacquer that has been mixed with silver or gold. The ceramic does not hide its broken parts, instead they are purposely visible and proudly displayed. The broken ceramic is beautified and the breakage is treated as an important part of the object’s history. In its broken state, it has transitioned into something more precious than it was before; it’s had a journey and has a story to tell. It’s OK to admit to being broken, because the truth is, some things hurt that much. But I’d like to see myself as an Kintsugi ceramic, broken but functional, with an unexpected and earnest inner enlightenment. Happiness, I have discovered, is so often fleeting, and sadness and melancholy can be poetic and beautiful in their discovery of human depth.

Kiran Sidhu

Kiran Sidhu is a British-Asian female pop philosopher, chronicling life. She is a freelance writer and a journalist for the Guardian, I Paper and Telegraph, to name a few. She has written a number of articles which have gone viral, creating international debate, the most notable being, ‘A dirty secret called grief’ and ‘Why I’ll be spending my golden years with my golden girls’, both written for the Guardian. She has made a number of appearances on radio to discuss the taboo subject of grief. Kiran has just written her debut novel, ‘The Waiting Room’ and is currently looking for a publisher.

Kathyrn Polley

Kathryn Polley is a photographer based in Helensburgh, Argyll & Bute. Winner of the 2017 Jill Todd Photographic Award and a Communication Design graduate of the Glasgow School of Art. Kathryn’s personal practice is an examination of the boundaries and territories we construct for ourselves to nurture a sense of belonging in the face of social, economic, mental and physical adversity.

Related Posts

Nothing found.