By Louise Xa

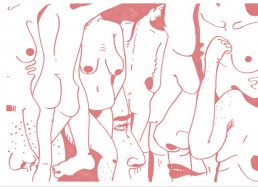

Illustration: Ida Henrich

If you are a woman, society sets one of your highest goals as being pretty. You think that sounds silly? I do too.

In Ancient Philosophy, humans began to be seen as entities made of two distinct parts – the mind and the body. In classical antiquity and beyond, men were usually associated with the mind and women with the body. One could guess this is because women have an obvious connection to their bodies. Besides the fact that they can create life within their own flesh, women also put up with frequent reminders of the existence of their bodies, through hormones, periods and so on. This association is obviously subjective, but it did not begin as negative or positive in the first place.

There are so many things we can explore within and through the body: art; relaxation; self-awareness; and body building – just to name a few. But the focus has rarely been placed on these.

After several centuries of disinterest for the body — it was seen as disgusting — the general idea slowly turned to the sexualized view we currently deal with on a daily basis. And because of the historical link drawn between women and the body, this sexualisation has been more heavily directed towards women’s bodies. Women are regularly turned into objects rather than subjects. A quick look at mainstream media is enough to confirm this idea: women are often shown solely as bodies; in some adverts a woman’s face is not even in the picture.

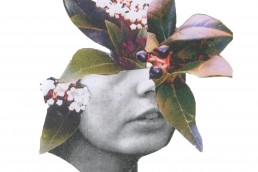

There is such a massive amount of attention on the female form and perfecting it that it seems to be the only goal that society deems important for women to reach. Whatever a woman’s successes are, the way she looks always seems to matter more (see the unavoidable comments on the appearance of singers, politicians, comedians etc.). Therefore, failure in this field seems excessively painful and harmful. Unfortunately, failure happens often, as no one can live up to the absurd list of requirements.

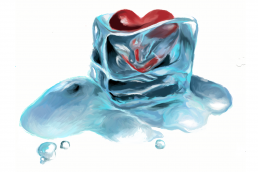

The pressures surrounding body image have been proven to trigger emotional distress, depression or anxiety in many women. The idealisation of skinny bodies has often been highlighted amongst the causes of body image distortions and eating disorders, and even when the extremes of an illness are not reached, the pressure of idealisation still puts women in danger of becoming physically as well as mentally unwell. I feel like this issue is not always taken seriously: the physical aspects of diseases, such as anorexia, are quite well known (and that’s great!), but the mental and emotional part still has to be recognized.

Fashion is a sector in particular that seems to persist in its skewed impact on women. For example, in the way fashionable outfits often limit women’s range of moves. From the historical corset that prevents proper breathing, to the more recent high heels that prevent running, or skirts that make it difficult to move. These criteria are usually omnipresent, especially – once again – in media. In movies or TV series, for instance, a positive male character has some flexibility in the choice of a socially acceptable body shape. From Michael Cera to John Goodman, including Danny Devito or Eric Elmosnino, there are multiple possibilities for the male spectator to find a character that looks like them. The actresses chosen to represent female characters have pretty much all the same body shape, because it is usually the only one accepted. As an example, I could name Jennifer Aniston, Keira Knightley, Emma Stone and Zooey Deschanel, but it could be any other actress, really. Fitting that one model seems to be essential for women; when you think about it, the main male lead of a movie doesn’t have to be attractive in a traditional way. He can be chiefly funny (Jack Black), clumsy (Michael Cera), nice, clever etc. Whereas, the female lead traditionally first has to be pretty according to mainstream standards in order to be accepted. Otherwise, they are usually shown as ridiculous. Rebel Wilson for instance is almost always cast in humorous sidekick roles.

Of course, there is this kind of pressure on men too, and that is a problem as well. But men have other options through which they can be seen positively in society. Women historically have only one, which creates an incredible amount of pressure and arguably provokes mental illnesses. In my opinion, it’s part of a casual sexism that despises everything associated with women: society makes you feel like, as a woman, you’re nothing if you’re not pretty; but it also tells you that focusing on being pretty is vain and silly.

It’s this pressure, this feeling of being trapped between two contradictory injunctions, added with the general lack of interest and education about mental illnesses that create such difficult times for women of all ages. It is not all bad though, there are really great efforts being made to improve the situation, with initiatives such as the World Mental Health Day, and body positive movements as just two examples of many. For me this issue is generally underestimated, and I hope that the interest raised about it in the past few years will keep improving our daily lives.

Louise Xa

Having graduated with too many degrees, Louise hasn’t decided yet what her field is. For now, she is curating exhibitions while editing a book and working as a librarian and a translator. Originally from France, Louise likes to spend time abroad (mostly to try out the food) and learn new languages. She is passionate about feminism and has a deep interest in everything related to genre, sexuality and bodies.

Ida Henrich

Ida Henrich is a German Cartoonist, Illustrator and Designer based in Scotland. She has worked with award winning publishers, online coaches and magazines. Ida is a graduate of Communication Design at the Glasgow School of Art where she specialised in Illustration. In her own work she explores themes such as sex-education, growing up, and women’s experiences. Her comics and illustrations are written for both men and women and aim to start an open dialogue between partners, friends, parents, and children about their experiences. Ida believes that Art is a powerful way to make ideas and feelings tangible.

As Art Editor at Fearless Femme, Ida is responsible for all things visual, including the correspondence with our visual artists, the design and realisation of the online magazine and the illustration of our amazing cover women. She also creates artwork for some of our articles, poems and stories.

Ida loves her coffee in the morning, that feeling after finishing an illustration and going for a run in the (Scottish) sun; and pilates on the rainy days. Ida enjoys SciFi books and autobiographies, and autobiographical comics. She is always delighted to meet new people on trains but is also smitten being home alone colouring in an illustration that she has made way too intricate while listening to Woman’s Hour. You can contact her at ida@fearlessly.co.uk.