Rachel Sharp

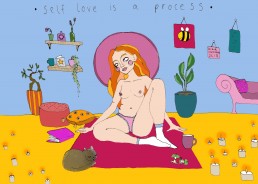

Illustration by Bee Anderson

There comes a point in every twenty-something’s life when they take a look around and are forced to reconcile who they are with who they thought they’d be. For me, it was a Tuesday morning in July. I was standing in the shower, passively letting the water run down me long after I was clean when it dawned on me that I wasn’t going anywhere.

I was an unemployed, university-educated twenty-four-year-old living rent-free in my parents’ house, filling my days desperately applying to jobs I didn’t even want because the slew of rejection emails from the ones I was actually interested in was taking its toll on my self-confidence. The stark dichotomy between where I was and where I thought I should be became a daily pill to swallow, and as one day seeped into the next, it became harder and harder to convince myself that I wouldn’t always feel this far behind.

Meanwhile, as I was schlepping through my twenties, Kylie Jenner, who’s three years my junior by the way, was adorning the cover of Forbes as America’s ‘youngest self-made billionaire’. ‘Another year of growth’, the article touted, and, ‘the youngest self-made billionaire ever, male or female, trumping Mark Zuckerberg, who became a billionaire at age 23.’

Twenty-three? What a chump.

The reality is that most of us won’t make the Forbes 30 Under 30 list, but with the conveniences and freedoms of being young in 2018, the pressure is on for us 20-somethings to achieve more faster and younger. We have an unhealthy obsession with youth, and Jenner is just one of a generation of ultra-successful overachievers spotlighted every year for making their mark on the world before they can comfortably rent a car.

Forbes and Inc each have their own annual 30 Under 30 catalogue, Fortune has an 18 Under 18 and a 40 Under 40 list, while Time is expected to release its sixth annual list of influential teens later this year. I get it, ’60 Over 60’ just doesn’t have the same front-page potential, but when we fail to celebrate the successes of those whose 20s are firmly in the rear view mirror, we perpetuate the misconception that time depreciates our self-worth and the value of our achievements.

It wasn’t until I started to write all of this down that I realised I had been thinking about my life as though it was over at 24. When today’s competitive climate dictates that we should do as much as possible as young as possible, it’s unsurprising we can feel lost when we don’t have everything figured out by the time we reach our quarter-life crisis.

That’s not to say I think we shouldn’t celebrate those who have accomplished so much so young. I’m just worried that the proliferation of ‘Under 30’ lists normalise the exceptional and make us resent the incredibly rare overachiever and the less rare over-privileged, well-connected-to-capitalism youth. It sustains a homogenised definition of success that fails to acknowledge any degree of subjectivity. Every time a magazine publishes one of these lists they idealise a career-centric culture that equates professional and financial goals with a fulfilling, successful life. By these standards, success has everything to do with financial security, job validation, property ownership and popularity, yet nothing to do with the pursuit of our passions or the strength of our moral fibre.

This materialistic, dehumanising approach is complete and total excrement.

That definition of success may have been applicable when there was money to be made and when a solid education was a passport to anywhere, but it means very little to a generation transitioning into adulthood in the current labour market. It’s outdated, one-dimensional and, frankly, just lazy. As David Foster Wallace eloquently put it in his 2005 Kenyon College commencement speech, ‘A huge percentage of the stuff that I tend to be automatically certain of is, it turns out, totally wrong and deluded’. With that in mind, we need to challenge how we define success so it’s relevant to young people pursuing it today.

Take, for instance, property ownership. In Britain we’ve been conned into believing that finding a rung on the property ladder is the objective for any self-respecting adult. But as we lament the relentless rise of housing prices, the rest of Europe doesn’t share our obsession with private ownership. Germany and Switzerland have two of the lowest rates of home ownership in the world, while in the Netherlands, around half of the population rents with housing associations. Simultaneously, these countries have some of the highest reported rates of happiness among their respective populations, as well as some of the most secure economies in the world.

We also assume that monetary wealth and professional validation are healthy means by which we can measure success. We assume that people who have achieved international recognition, made positive contributions to their fields, and in turn, earn a lot of cash for their efforts, are successful. Yet even the most celebrated among us suffer the same feelings of doubt and inadequacy. David Foster Wallace, award winning writer and Pulitzer Prize finalist, committed suicide three years after delivering the speech I quoted earlier. More recently we have the tragic deaths of Robin Williams, Kate Spade and Chester Bennington, all of whom ended their own lives in spite of their talent, wealth and global admiration.

If the deaths of apparently successful people suggest anything it’s that nothing materialistic means squat in the grand scheme of things. We need to ask ourselves if we truly want the holiday home in France, or do we feel as though we should have it because owning property has been sold to us as the holy grail of self-fulfilment? Do you want to make the Forbes 30 Under 30 list, or is it because the people smiling back at you from the glossy pages look happier than you feel? Success isn’t necessarily the career, the car or the cash; it’s the constant pursuit of our best and happiest selves, the thinking back to what made us happiest as kids or whenever we felt most free and it’s the hard work involved in determining what that looks like for each of us and then going for it.

Rachel Sharp

*please note that this article recently appeared on the Scottish Review website http://www.scottishreview.net/RachelSharp442a.html

Rachel is a Glasgow-based freelance writer who struggles to write short bios that don’t sound like rejected ideas for dating profiles.

Bee Anderson

Bee is a 20-year-old artist from Devon, and is currently studying a BA(Hons) in Illustration at The University of Edinburgh. She has been working primarily as an illustration based artist for the past three years, although she has dabbled in a variety of the arts throughout her life.

Bee’s art primarily explores provocative themes of eroticism, mysticism, sexuality, feminism and politics, and she is passionate about evoking feeling in others within her work. Bee takes inspiration from the likes of Tracey Emin, Egon Schiele, Kaethe Butcher and Liselotte Watkins – all of whom have distinct and equally unique styles and methods of working within their individual mediums. Bee strives to depict striking, fierce images of goddess-like women, and through them, empower and inspire her audience.