by Charley Hines

Image credit: Ida Henrich

For a while, my periods were near impossible to handle.

Excruciating cramps, nausea so intense I had to take days off to curl up in bed with ibuprofen that wouldn’t touch the pain, and wait it out. Mood swings, exacerbated by severe depression, that were so intense I hardly knew myself. Fed up of this monthly uproar, I visited the GP and was, with no discussion, recommended the Microgynon pill, later widely replaced by Rigevidon.

The months passed. I ploughed into Cognitive Behavioural Therapy to deal with my depression. Slowly the clouds lifted, but something was still off. I was set upon by intense and crippling anxiety. I had always had intrusive thoughts, and they now intensified to violent and near constant bursts of mental activity that left me too fearful to leave the house, to sleep in a new bed, to talk to people. I felt terror and despair that I can still taste on the tip of my tongue when I remember that time — of coming to the end of this long and winding road to recovery and coming face to face with this wild, spitting, unstable thing that no amount of therapy, breathing exercises, or care could touch.

At the end of it all, under the darkness, was this me? I was reassured that this was normal and that, as people recovered from depression, they tended to slip into a bout of anxiety that would soon pass.

It did not pass. Fast forward four years — four years of slowly coming back to my senses (for as many who have dealt with the Black Dog will know, the opposite of depression is not Happiness, but Feeling), and grappling fruitlessly with bursts of unwarranted anger and unbridled terror. I developed a painful lump on my leg. The lump had appeared at the site of a major varicose vein operation ten years previously. My case was startlingly bad for someone of my age and this sudden flare up was cause for great concern, especially as cases of women’s lives being ended prematurely because of pill-related blood clots had begun to permeate the press.

The lump was thankfully not a clot, but a case of phlebitis (inflammation of a vein). Nevertheless, my GP told me to come off the pill immediately.

It was like a bag had been pulled off my head. The anxiety evaporated overnight, leaving me with a clear view of the world for the first time since my pre-teen years. Looking back over the scarred landscape of my time on the pill, I could not comprehend how someone with a history of mental health problems and a heightened risk of blood clots could have been put on a medication which aggravates both of those things. It had not even occurred to me that the pill was causing the anxiety.

I want to make something clear: the pill itself is not the villain here. The pill was instrumental in our fight for sexual freedom, and it works very effectively for many people who take it for a variety of purposes. However, there are major flaws that for some reason are being swept under the rug at great cost to many.

It’s not only the willingness with which we accept the side-effects — it’s the appalling lack of communication from GPs to young people about what they’re taking. It’s the societal shrugging-off of the side-effects of not only the pill, but of periods in general, the glamorisation of the monthly struggle. It’s the total absence of any kind of check-up procedure. When we’re prescribed antibiotics, we’re told to “make another appointment in two weeks and we’ll see how you’re getting on”. Why is there no such advice (if not from the NHS, which is, as we know under enormous strain), from schools, from colleges and universities, from parents and guardians?

Of course, part of the reason why is becoming more apparent. It’s the old assumption that high emotion is part of what it is to be female, that the very fact contraception is available in the first place is enough to warrant us putting up with the side effects.

We are given a cruel ultimatum: you can have your physical health, or your mental health. Choose.

What if we could have both? What if there was more science being dedicated to developing new contraceptive pills that are safer, and alternatives for those for whom the pill is too problematic? How do people get access to information about the options that already exist? There can and should be a contraceptive pill that is clean and safe. There can and should be information that is detailed, accessible and given as standard procedure. There is so much more that could be done.

For starters, parents and guardians must be more communicative. Time for the generation who grew up believing that one did not discuss such things to start talking with their children — letting them know that depression, anxiety, sex and periods are not dirty words. There is no time for outdated and repressive sensitivities around these topics. People are dying, suffering, losing years of their life to poor mental health, thinking they must choose between one pain and another.

As pill users, past pill users, and as alternative remedy users we can speak up. What is working for you? What isn’t? Does that correlate with other users of the same method? Reach out to those in need of support, answer what questions you can. Your experience is valid, your story is useful, your feedback is needed. We can become better communicators with our bodies this way — more understanding, more accepting, more passionate about our wellbeing. We will make more informed decisions, and we’ll know better when something isn’t working.

We deserve both the right to our own bodies, and the right to safe methods of supporting our bodies. Time for the next step.

Charley Hines

Charley is an actor and broadcaster living in London. They have recovered from severe depression and anxiety, and they are working to improve the mental health conversation within the performing arts business. When Charley isn’t treading the boards, they can be found ukulele-playing, clarinet-tooting, book-reading, puppet-wrangling and city-walking.

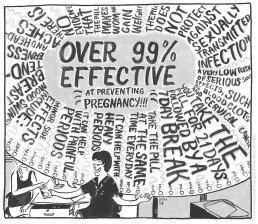

Ida Henrich

Ida Henrich is a German Cartoonist, Illustrator and Designer based in Scotland. In her own work she explores themes such as sex-education, growing up, and women’s experiences. Her work is written for both men and women to read and aims to start a dialogue between partners, friends, parents and children. Her graphic novella, Minor Side Effects, is currently in its first edition and she hopes to bring out the next soon. Ida is a graduate of Communication Design at the Glasgow School of Art. A big influence on her work is Julie Doucet, with her brilliant autobiographical comics. Ida is currently working on a number of commissions including illustrations for short stories and businesses.