by Jessie Jane Johnson

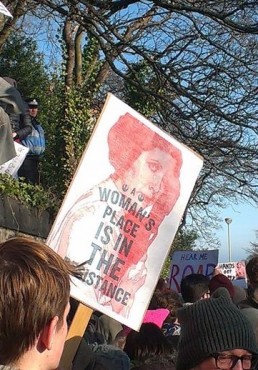

Image credit: Bonnie Calderwood Aspinwall

Content Warning: discussion of sexual violence/assault statistics

2018 is a year filled with significant anniversaries for the development of women’s rights. On the 2nd of February it was 100 years since the UK first gave (some) women the right to vote. Likewise, on September 19th it will be 125 years since New Zealand became the first self-governing country to grant full women’s suffrage.

In the time that has passed since, societies all over the world have been changing for the better with regard to gender equality. In the UK women have gained the right to stand as an MP and numerous laws have been passed which, among other things, make it illegal to discriminate against women in work, education and training. In America, the story is much the same, over the past 30 years more and more women from all kinds of backgrounds have taken up powerful positions in government and business, women are now allowed to have combat positions in the military, and services for victims of rape and domestic violence provide women with the ability to get help with gender-related crimes.

However, this is not yet a story of success. This is a story of women and men fighting battles against tradition, expectations and stereotypes but not yet ‘winning the war’. 2018 is a year of milestones, a year to recognise how far we have come and to give thanks to the fearless women and the outstanding men that have helped us get to this point. Yet, it is also a year to focus our concentration and our energy on the women who still do not have the basic rights that are owed to them — women’s rights are, after all, human rights.

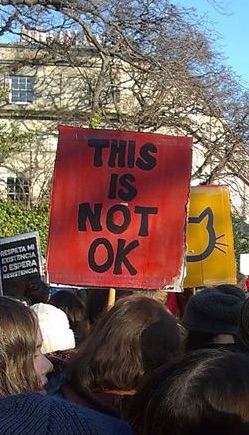

Over the past few months major events have happened which can make it easy to feel that the world and its global society has taken a step backwards. According to Forbes Magazine, the two most powerful people in the world are Vladimir Putin and Donald Trump — two men who have gained the media’s attention for their misogynistic and divisive personalities.1

Over the past few months major events have happened which can make it easy to feel that the world and its global society has taken a step backwards. According to Forbes Magazine, the two most powerful people in the world are Vladimir Putin and Donald Trump — two men who have gained the media’s attention for their misogynistic and divisive personalities.1

In her book We Should All Be Feminists, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie pointed out that, even though 52% of the world’s population is female, most of the positions of power and prestige still belong to men2; since Trump’s inauguration, the US presidential administration contains the fewest women of any since the 1980s, a fact which Adichie admits makes her angry.3 She describes gender imbalance as a “grave injustice” and goes on to argue that we should all share this emotion as “anger has a long history of bringing about positive change”.

In a world where we have come so far yet still have such a ways to go, it can be difficult and even daunting to recognise what these first changes should be. My argument is that we start from the bottom up. Instead of focussing everything we have on getting the women in developed countries ‘on top’ we should send our energy to the women who still don’t have power over their own bodies and everyday choices. Gender inequality has far-reaching effects. Some are obvious — for example the right to decide whom you marry and the right to choose what happens to your body — but others are too-often invisible, like the grave effects this inequality has on women’s mental health.

The Industrial Psychiatry Journal (IPJ) outlined in 2012 that “economic independence, physical, sexual and emotional safety and security” are all needed to have a good mental health.4 Unfortunately, these things are still denied to women in many parts of the world simply by virtue of being women. Kim Stacey, who has been working as a counsellor in England for the past 12 years, agreed that “gender is a significant determinant in mental health issues”. Stacey pointed me towards an article where the World Health Organisation (WHO) reported that of the most common mental illnesses — depression, anxiety and somatic complaints — women are the majority of sufferers.5

Now, this could be for a number of reasons and it cannot be argued that this is solely due to gender inequalities. However, gender, and the pre-set perceptions that go with it, determine the power that women have over the social and economic aspects of their lives. According to WHO this includes “their social position, status and treatment in society and their susceptibility and exposure to specific mental health risks”.6 An example of this comes from Vikram Patel who noted in his journal on poverty, gender and mental health that interpersonal networks and, most importantly, social identity are two of the leading factors in female suicides in rural China — something that has become much more common in recent years.7

The social identity of women in countries with a deeply misogynistic tradition or culture has been proven to have an effect on their emotional security. Going back to the IPJ’s list of factors needed for good mental health (to which many have added access to education), we can begin to understand why this is the case.

Let’s start with economic security; the organisation UN Women conducted research that found that 90% of 143 studied economies had a legal difference which restricted women’s economic opportunities. Of these, 79 economies have laws which restrict the types of jobs women can have and, in some extreme cases, they even found that in 15 economies husbands can object to their wives working and have the right to stop their wives from accepting jobs.8 It is because of this, they argue, that women become family workers and if they do gain employment they are more likely to work in the informal sector or in vulnerable, low-paid or under-valued jobs. In rural areas especially, this is more often than not in the farming industry.

Phoebe Asiyo, a former parliamentarian of Kenya and ambassador to the United Nations Development Fund for Women, was quoted in the Independent in 2010 saying: “Women are still more likely than men to be at risk of hunger, because of systematic discrimination. It is unacceptable that, though poor women produce the majority of food, they make up the majority of the world’s hungry”.9 Not only this, UN Women also found that when paid and unpaid work is combined, women in developing countries work more than men with less time for education, leisure, political participation and self-care.

This takes us on to the second factor: education. Education gives us a knowledge of the world around us, enabling us to create our own perspectives and opinions — it is the foundation upon which we build our own personalities and characters. On a more functional level, without a good education or recognised qualifications, we are much less likely to land a good job with a secure income or be able to participate in political and social movements.

UNICEF found that of the 132 million children that are out of education around the world, 60% are girls.10 Feminist and volunteer for the Young Women’s Movement in Scotland, Katie Williams, spoke with me and said that a lack of education is by far one of the “greatest challenges women in developing countries face”. Sadly, in the vast majority of these countries, a girl’s ability to be a mother and a wife are valued above this. In Cambodia, for example, most women’s education comes to a halt at the onset of puberty — if not before — and in India a girl’s virginity and purity are deemed more important than her education. Journalist and TV presenter, Esther Rantzen, said in 2010: “I’m very aware that the freedoms I was brought up to believe in — equality of education, equality of ambition — are not available to all women, even in the UK”.

In the UK our education system hammers into our minds from a very young age that a person’s body belongs to them and them alone. We move from primary school, to secondary and from there to university with this knowledge and we have a sense of security because of this. We can walk down the street alone at night, climb into bed with our partners in the evening and feel safe, or at least, this has been my experience. Sadly, domestic and sexual violence infects almost every country, no matter how developed, and gender-based crimes against women are on the rise. Of course, this rise may be due to the media attention the topic has received, encouraging women to come forward about their experiences and to seek help; however, the numbers are still significant. Kim Stacey commented on this saying “in my work at the Women Centre we are very aware of gender-based discrimination. At least 60-70% of women we see there have issues relating to domestic violence and sexual violence. It sadly seems to be increasing”.

This is something that can be seen all over the world — globally, over 35% of women and girls experience sexual violence. Surveys in Uganda reported that more than 80% of female patients receiving trauma-focussed treatments in hospitals reported at least one sexual assault in their lifetime.11 In the last 20 years alone, an estimated 17.7 million women in America have been victims of rape.13 It is important to note here that men can also be victims of sexual violence and this should not go unnoticed; however 82% of juvenile and 90% of adult victims of sexual violence in the US are female.

And yet, the trauma of this gender-based violence doesn’t end with the act itself. Mental Health America (MHA) reports that sexual assaults can leave the survivor with a variety of short and long-term mental health issues.13 These include, but are not limited to: depression, PTSD, substance use disorders, eating disorders and anxiety. In developed countries, a survivor will have access to helplines, healthcare and support groups, all there to aid them through their recovery. However, in developing countries these women will fear even mentioning that what has been done to them. Journalist Yemisi Akinbobola wrote about this in one of her articles for Africa Renewal, following the gang-rape of a woman in Nigeria.14 She said that the “majority of sexual violence in Nigeria [goes] unreported. This is due largely to fear on the part of the victim of being socially stigmatised or blamed”. Akinbobola goes on to explain that at least 2 million girls experience sexual assault in Nigeria per year, but only 28% of these cases are reported and of those only 12% end in conviction. And so here we can find evidence of a lack of physical and sexual security which, in many cases, results in a lack of emotional security too — the remaining attributes given by the IPJ.

For those of us fighting for gender equality, there remains a long road ahead. Knowing that gender inequality continues to scar the lives and minds of women all over the world makes this fight more important than ever. This article has focussed on just one part of this destruction — mental health. This International Women’s Day we can pause and celebrate our progress. But we should also take a moment to pay tribute to the women who do not have the rights they deserve. Let us think of the women and men who are thriving in cultures too often bound by the ropes of tradition and old-fashioned thinking. Let’s move forward with the promise of the women who have come before us and work tirelessly for a future that encompasses the needs and wants of everyone equally. A future where we all might rest and say to our daughters — ride on.

1 The World’s Most Powerful People List, Forbes Magazine, 2016

2 Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, We Should All Be Feminists, 2014 (published by Fourth Estate)

(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Forbes_list_of_The_World%27s_Most_Powerful_People)

3 Jasmine C. Lee, The New York Times, Trump’s Cabinet So Far Is More White and Male Than

Any First Cabinet Since Reagan’s, 2017 (https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/01/13/us/politics/trump-cabinet-women-minorities.html)

4 Industrial Psychiatry Journal, Women and mental health: Psychosocial perspective, 2012

(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3678171/)

5 World Health Organisation, Prevention of Mental Disorders, 2004

(http://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/en/prevention_of_mental_disorders_sr.pdf)

6 World Health Organisation, Gender and Women’s Mental Health, 2018

(http://www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/genderwomen/en/)

7 Vikram Patel, Poverty, gender and mental health promotion in a global society, 2005

(http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/10253823050120020104x)

8 UN Women, Facts and Figures: Economic Empowerment, 2017

(http://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/economic-empowerment/facts-and-figures)

9 Independent, The Rights of Woman: How far have they advanced?, 2010

(http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/politics/the-rights-of-woman-how-far-have-they-advanced-1917579.html)

10 UNICEF, Equality, development and peace, 2000

(https://www.unicef.org/publications/files/pub_equality_en.pdf)

11 Janice K. Kopinak, Mental Health in Developing Countries: Challenges and Opportunities in

Introducing Western Mental Health System in Uganda, 2015

(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4948168/)

12RAINN, Sexual Violence Affects Millions of Americans, copyright 2018

(https://www.rainn.org/statistics/victims-sexual-violence)

13 Mental Health America, Sexual Assault and Mental Health, copyright 2018

(http://www.mentalhealthamerica.net/conditions/sexual-assault-and-mental-health)

14 Yemisi Akinbobola, Social media stimulates Nigerian debate on sexual violence, 2011

(published by Africa Renewal)

(http://www.un.org/en/africarenewal/newrels/nigeria-sexual-violence.html)

Jessie Jane Johnson

Jessie is a teacher, writer, sailor and traveller. Currently studying at the University of Stirling, Jessie grew up in Scotland, was born in The Netherlands and lives all over the world (on land or at sea)! Known more commonly as Messy Jessie, this girl is passionate about equality, the environment and all things creative. When she isn’t struggling over an essay in the library, you’ll probably find her somewhere knitting, reading, or dreaming about the next adventure.

Bonnie Calderwood Aspinwall

Bonnie is a genderfluid writer-adventurer from Scotland (and England and America). She studied at the University of Edinburgh and l’Université Paul-Valéry-Montpellier. She is passionate about mental health, intersectional feminism, gender and sexuality, and much more. She is probably swing dancing, binge-watching Media Content (no spoilers), or trying to read 50 books in a year.